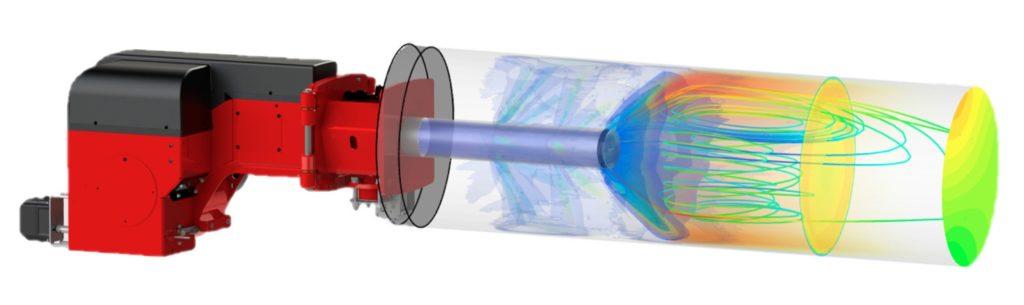

Computational fluid dynamics, CFD in short, is primarily used for numerical modeling of gas and liquid flows. CFD enables Oilon’s experts to simulate different processes, such as a burner’s operation far ahead of building a physical prototype. This speeds up and reduces the cost of development, and the end result is better overall.

Nitrogen oxides (NOx compounds) are gases made up of nitrogen and oxygen. These compounds react with hydrocarbons in the atmosphere, forming fine particles. Both the gaseous NOx emissions and these secondary particulate emissions cause respiratory problems, increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, and have various other harmful effects. They also contribute to soil and water acidification and eutrophication and are harmful to plant life.

Global race to reduce NOx emissions

Nitrogen oxides are formed in all types of combustion. However, the main sources are traffic and energy production. When combustion occurs at high temperatures, oxygen and nitrogen react with each other, forming nitrogen oxides. The bulk of these oxides are released as nitrogen monoxide (NO), which will gradually oxidize in the atmosphere, forming nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and other nitrogen compounds.

Years of study have revealed three major formation mechanisms for NOx: fuel, thermal, and prompt. In the first process, organic hydrogen present in fuels is oxidized, forming NOx. Fuel oils and, in particular, coal, have a high nitrogen content. Combustion and boiler technology can be used to reduce the amount of NOx created from organic nitrogen. However, due to high initial concentrations, flue gas scrubbing (SCR) is also often required.

Thermal NOx, in turn, is formed when the bonds within a nitrogen molecule break down at a high temperature, and the released nitrogen atoms become oxidized. This formation mechanism can be effectively addressed with combustion technology. Consequently, when firing fuels that do not contain organic nitrogen (e.g. natural gas), low emission levels can be achieved without after treatment.

The third mechanism, prompt NOx, is associated with the ratio of fuel and oxygen within the furnace; typically, this process produces considerably fewer emissions than the former two.

Nations around the globe are increasingly reducing their NOx emissions. This requires continuous advances in combustion and boiler technology, but there is also another factor to consider: which fuel to use. Oilon has made developing Low-NOx combustion technology a priority, and, in recent years, the company’s efforts have focused especially on low-NOx solutions for natural gas. Let’s take a look at one example.

LN30 Ultra low NOx – a new family of burners

“This is where the magic happens, in the combustion head,” says Joonas Kattelus, R&D Director, Combustion Technology at Oilon Oy. “Last spring, we introduced the all-new Monoblock LN30 product family. When firing natural gas in these burners, we can achieve the ultra-low NOx limit, 9 ppm, going down to 5 ppm and beyond. These are premix burners with a long, tubular combustion head. The smallest member in the family has a maximum capacity of 900 kW (3.4 MMbtu/h) and the largest, 4.9 MW (18.6 MMBtu/h). These are industrial burners, and represent our mid-range models; power plant burners are a topic for another day.”

“There have been other premix burners on the market for years already; however, what we are now offering is considerably better than any previous models. For example, let’s compare our new solution to pre-mix mesh burner technology, where the fuel–air mixture is homogenized as much as possible by feeding it into the furnace through a tight mesh. Our LN30 burners have no mesh; instead, we use a long tube with nozzles at the other end for feeding the fuel and air [into the furnace] for combustion.”

Kattelus explains that a mesh-based burner requires extremely clean combustion air, as otherwise impurities would clog up the mesh in the combustion head. In practice, effective filtration is a must, and the filter itself would require frequent cleaning. This technology cannot be used in dusty environments. The burners in the LN30 series have no filter; no filter is required, as there are no small openings prone to clogging.

Low NOx emissions at low residual oxygen levels

“One significant new characteristic of the LN30 series is its reduced residual oxygen (O2) level,” Kattelus continues. “In traditional premix burners, the 9-ppm NOx limit can be achieved only with a 7–8% residual oxygen level. We can achieve this with an O2 level as low as 4–6%. At 6–8 % O2, we can go as low as 5 ppm. Naturally, our goal is to get the residual oxygen level as low as possible, as this will improve efficiency.”

“We were able to fine-tune our premix very close to perfection, resulting in a major boost in performance. We’ve developed the mixing process entirely with CFD. By selecting the right shape for the combustion head and the nozzles, and with proper nozzle placement, we managed to keep the flame extremely compact. The flame fits well even in a smaller furnace.”

Kattelus elaborates that a perfect premix will also reduce the risk of CO formation. Typically, when NOx levels go down, CO levels go up. With a perfect premix, all CO is consumed and the problem is avoided.

Another benefit of a long combustion head is that it promotes internal flue gas recirculation (IFGR) in the front section of the furnace. In this process, inert flue gas is mixed into the fuel–air mixture. This cools down the flame, reducing the formation of NOx compounds.

“Traditionally, flue gas mixing has been achieved using external flue gas recirculation (FGR), where flue gas is fed into the furnace from the outside. This requires separate ductwork, a control valve and possibly a fan for transporting the flue gas, resulting in a higher initial cost. Another problem in these kinds of applications is condensate, which causes corrosion in the equipment, shortening its useful life. Moreover, FGR reduces the burner’s capacity.”

According to Kattelus, Oilon has verified its new burner family’s delivery reliability and performance with extensive laboratory testing. The products have also been UL-certified. Currently, the company is in the process of piloting the burners with reference cases across the United States. The company’s been delivering LN30 products in other markets for a couple of years, and the results have been good. Oilon has patents pending for the new technology in Europe, North America and China.

CFD-modeling is the key to excellent engineering and development

For almost 15 years, Oilon has utilized CFD calculation in burner engineering and development. Today, CFD is one of the main development tools used at Oilon. In the early ears, CFD calculations took a long time to process and tended to deliver inaccurate results, and the tool was relegated to a supportive role. However, as processing power increased, computational models matured and the company’s know-how expanded, CFD became more viable, and has now served several years as the company’s primary development tool.

“Today, we develop our products largely using CFD simulation. In most cases, the values we get are pretty much exactly the same as those from testing the actual physical prototype,” Kattelus says. “We used to make several of prototypes during burner development, and testing each of these took a long time. Now, thanks to CFD, we get better results faster and with fewer costs, even in a landscape rife with increasingly stringent requirements. On one hand, the boiler industry tends to keep furnace sizes as small as possible to reduce costs, and on the other, legislation aims to reduce emission levels. There is a conflict between these two, as a smaller furnace will increase NOx emissions.”

“Naturally, both boiler performance and the amount of NOx emissions depends on both parts of the sum: the burner and the furnace. Emission levels depend on several parameters, but the main rule is that improving the transmission of heat from the flame to the furnace will always reduce NOx emissions. There are many ways to improve this, such as optimizing furnace dimensions, furnace corrugation, and minimizing the use of refractory. CFD modeling allows us to work with boiler manufacturers to ensure the best possible result.”

Unique CFD know-how and an excellent laboratory

Over the years, Oilon has acquired an extensive experience and a unique know-how in utilizing CFD-modeling. This expertise is supported by excellent laboratory facilities in the company’s product development center. These form a combination that is hard to beat: measurements from the laboratory are used to develop CFD models, which, in turn, are verified and further tested in the laboratory. According to Kattelus, the company has the world’s most advanced natural gas combustion models, especially when it comes to emission modelling.